Features Links

Advising Students Student Councils

Student Councils  Junior Press

Junior Press Environmental Issues

Wild Ireland

Wild Ireland Rubbishing Ireland

Rubbishing Ireland Issues of Concern

Children's Rights

Children's Rights  Child Labour

Child Labour  Child Slavery

Child Slavery  Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia Nervosa Educational Issues

Learning the Internet

Learning the Internet  History Stuff

History Stuff  What is Quidditch?

What is Quidditch? Getting Involved

Paths to Peace

Paths to Peace  Concern Debates

Concern Debates  Goal Link

Goal Link  The Asgard

The Asgard Music

JJ72

JJ72  Napster

Napster  Eminem

Eminem Sport

Basketball Finals

Basketball Finals News

Nationwide News

Nationwide NewsClare Holohan reports on a phenomenon created by economics.

Cocoa Plant Slaves

Boys work for nothing in the Ivory Coast.

Iqbal's Dream

The remarkable story of a Pakistani boy who escaped slavery and helped many others to freedom.

A Bullet can't Kill a Dream

A teenager who brought about real change

Slave Labour: A Reality in the 21st. Century

Trafficking is the transport and trade of usually

women and children for economic gain using force

or deception. The women are tricked into domestic

labour or prostitution.

Article 4, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

According to Anti-slavery International there are at least 26 million slaves in the world at present. People - especially children - can be enslaved today for as little as US$25. Bondage labour or debt bondage is the most widely used method of enslaving people. It begins when a person takes or is tricked into taking a loan for as little as the cost of medicine for a sick child or some food. To repay the debt they are forced to work long hours, seven days a week, 365 days a year. Take an 11-year old boy in India as an example. He has been placed in bondage by his parents in exchange for about US$35. He now works 14 hours a day, seven days a week making beedi cigarettes. This boy is held in 'debt bondage'. The boy and all his work belong to the slaveholder as long as the debt is unpaid, but not a penny from his work is applied to the debt. Until his parents find the money, this boy is a cigarette-rolling machine, fed just enough to keep him at his task. Most people in bonded labour receive basic food and shelter as 'payment' for their work, but may never pay off the loan, which can be passed down through several generations.

Forced labour affects people who are illegally recruited by governments, political parties or private individuals and forced to work – usually under the threat of violence or other penalties. This type of labour applies especially to the estimated 800,000 people in Burma who are forced to work by the military regime. Trafficking is the transport and trade of usually women and children for economic gain using force or deception. The women are tricked into domestic labour or prostitution. Sexual exploitation puts a commercial value on a child. They are often kidnapped, bought, or forced to enter the sex market. It is a fact that up to 2 million women and girls worldwide are victims of a growing trade in forced labour within the sex industry. Other forms of the worst child labour refer to children who work in exploitative or dangerous conditions. Tens of millions of children around the world work full time, depriving them of education and recreation crucial to their personal and social development. In Sierra Leone, children as young as seven are captured by armed groups and trained as soldiers.

For the most part, slaves work at the most basic of tasks: mining, logging, farming, begging, hauling goods, breaking stone, herding and prostitution. But their labour feeds into our economies. Some charcoal in Brazil is made by enslaved workers and charcoal is a key ingredient in Brazil's steel production, the country's second largest export. The steel goes into everything from toys to skyscrapers and especially cars and furniture. Our chocolate comes from cocoa harvested by slaves in the Ivory Coast, most of who have never tasted chocolate in their whole life. Our carpets are made by child workers in Pakistan. We enjoy a lower price for these goods because of the slave input, while the slaves themselves earn little or nothing.

Slavery exists today despite the fact that it is banned in most of the countries where it is practised. It is also prohibited by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 1956 UN Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery. Despite this, many governments are unwilling to enforce the law or to ensure that those who profit from slavery are punished. Many countries claim that they are ‘slave-free’ when they are clearly not. In India, declarations by state governments that that they have eradicated debt bondage have given up on the struggle to liberate other bonded workers. Under Indian law, a freed bonded labourer is entitled to compensation and a rehabilitation grant. But when states are 'slave free', local officials are reluctant to tarnish their record by reporting workers in bondage. Modern slavery differs from the past in one special way: Slaves today are cheaper than ever in human history. In the same way that mass production lowered the cost of what we buy, overpopulation has made slaves plentiful, cheap and disposable. In 1850, an average agricultural slave in Alabama sold for $1,000, around $40,000 in today's money. A child in India can be sold into bondage for as little as £25 today.

There are many forms of exploitation in the world, many kinds of injustice and violence. But slavery is exploitation, violence and injustice rolled into one. What good is our economic and political power, if we cannot use it to free slaves? But what can we do to help? Trocaire's Lenten Campaign this year was to fight slavery. They work with the local partners in the country to free bonded labourers and they set up projects for them to help bring their lives back to normality. Their work cannot be done without the support of the public. Trocaire has also distributed postcards that can be sent to the International Labour Organisation (ILO). Other ways we can fight slavery is by purchasing Fairtrade Mark products such as coffee, tea, honey and chocolate which is on sale in Oxfam shops nationwide. They can guarantee that bonded labour is not used in any part of their manufacture. Rugs should be purchased with a 'rug mark label' on it to make sure that it has not been made by exploited children and we can also contact manufacturers to guarantee that chocolate does not have its origin in the horror that is slavery.

It is surely not too radical to say that our dignity as civilised human beings can only be preserved by a determined worldwide struggle to eliminate modern slavery in all its forms.

Written by Clare Holohan, Loreto Abbey Dalkey Secondary School, Dalkey, Co.Dublin.

Back to the top

Cocoa Plant Slaves

A British television documentary has revealed the desperate plight of many workers on cocoa farms in West Africa - source of much of the world's chocolate. The makers of Channel 4's Slavery series say more people now live in a state of slavery than at any time in history.

They support their assertion with reports from the United States, Britain, India and the Ivory Coast.

A British television documentary has revealed the desperate plight of many workers on cocoa farms in West Africa - source of much of the world's chocolate. The makers of Channel 4's Slavery series say more people now live in a state of slavery than at any time in history.

They support their assertion with reports from the United States, Britain, India and the Ivory Coast.The film makers say every country in the world has laws against slavery, and yet hundreds of thousands of people, most of them very young, work without pay, without the freedom to leave their job, and are often beaten and intimidated by their employers.

Two of the cases highlighted by the programme have been publicised in the past - those of children in Indian carpet workshops, and domestic workers brought by their employers to Europe and the US. Less widely know is what happens on the cocoa farms of the Ivory Coast. Ivorian cocoa plantations need a lot of labour. Migrant labourers from neighbouring countries, particularly Mali, have always worked the cocoa plantations.

Two of the cases highlighted by the programme have been publicised in the past - those of children in Indian carpet workshops, and domestic workers brought by their employers to Europe and the US. Less widely know is what happens on the cocoa farms of the Ivory Coast. Ivorian cocoa plantations need a lot of labour. Migrant labourers from neighbouring countries, particularly Mali, have always worked the cocoa plantations.In the past, they would be contracted for the farming season, and at the end when the farmer sold his crop, they would get their pay and return home. But cocoa prices are at a ten-year low and deregulation of the market has made it harder for farmers to get their money. Less scrupulous farmers have stopped paying their workers altogether. The Malian consul in the Ivory Coast has had to rescue boys who had worked five years or more without payment and who have been brutally beaten if they tried to run away.

The programme makers say the solution ultimately lies in the hands of consumers. They say people have to be prepared to pay a little more for their chocolate or their carpets, since it is the relentless downward pressure on prices which reduces workers to poverty and slavery. British chocolate makers have promised to investigate the allegations made in the programme.

Back to the top

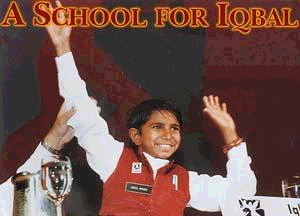

Iqbal's Dream

Iqbal Masih (pictured above) was four years old when his father sold him into slavery for the equivalent of $12. He was forced to work more than twelve hours a day. He was constantly beaten, verbally abused, and chained to his loom by the carpet factory owner.

There are an estimated 20 million bonded laborers in Pakistan today; at least 7.5 million of these bonded laborers are children. More than 500,000 children, like Iqbal, work in the carpet industry. Because carpet factory owners, usually rich and influential men in their communities, are often under the protection of the local police, laws against enslaving children are seldom enforced.

In 1992 Iqbal's life changed dramatically. He and some other children stole away from their carpet factory to attend a freedom day celebration held by the Bonded Labour Liberation Front (BLLF). At the gathering they learned about their rights. Iqbal was moved to give an impromptu and eloquent speech about his sufferings which was printed in the local papers. Afterwards he refused to return to his owner. On his own initiative, he contacted a BLLF lawyer and obtained a letter of freedom which he presented to his former master.

Iqbal was an articulate, confident, and powerful speaker and an uncompromising critic of child servitude. Iqbal's words of encouragement to other children and his willingness to speak out against child slavery had helped free many other illegally bonded children.

On December 2, 1994, Iqbal visited the Broad Meadows Middle School in Quincy, America. He looked much younger than his twelve years: his growth had been stunted by severe malnutrition and years of cramped immobility in front of a loom. The pupils at the school were greatly moved by the plight of children forced into slavery. Elizabeth Bloomer was a pupil at this school. You can read her story in the panel opposite. The pupils wrote letters and poems and drew posters, some of which are displayed on this page. Iqbal won the Reebok Human Rights Youth in Action Award 1994.

On Easter Sunday, 1995, Iqbal was murdered. He was probably gunned down by a mafia group associated with the carpet factories. At the time of his death, he was enrolled in a school for freed bonded children, where he was a bright and energetic student. His dream for the future was to become a lawyer. That way, he reasoned, he could continue to fight for freedom on behalf of Pakistan's seven and a half million illegally enslaved children.

Thoughts of a school student when hearing of Iqbal's death

Jim Cuddy (age 13), Broad Meadows Middle School

Poem dedicated to Iqbal

My life vs. Iqbal'sby Ryan Krueger

My childhood was a ball

when I was four I played cars and games

when Iqbal was four he worked with fibers and chains

at five years of age I started school

Iqbal finished a rug

at age seven, eight and nine I would run and have fun

Iqbal would only work through the din and the pain

on my tenth birthday I went on a trip

Iqbal made his escape

my childhood was a good time

Iqbal's childhood was a crime

Back to the top

A Bullet can't Kill a Dream

Elizabeth Bloomer is a typical teenager, putting her jeans on one leg at a time. But she checks the label first to make sure her clothes are not from a country or company suspected of using child labor.The 15-year old has so passionately pursued the fight to end child labour abuses worldwide and has become such a well-spoken advocate that she has addressed the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York, sharing the day with more famous speakers.

While school projects come and go, young attention spans wane, and trends change quicker than you can say "New Kids on the Block," Bloomer has held on tightly to the cause she and her classmates took on four years ago as students at the Broad Meadows Middle School in Quincy. It began with a story about a little Pakistani boy. Twelve-year-old Iqbal Masih freed himself from slavery in a carpet factory, fought to get more than 3,000 other children to do the same, came to the United States to accept an award, and became a symbol of the fight against child labour, only to be murdered while riding his bike outside his grandmother's house in Pakistan on Easter Sunday 1995.

When Bloomer first heard Masih's story, she was moved to stamp out child labour. She hasn't stopped moving since. "I know it's real, and it's not just something that happens in another country where I can't do something about it," insists Bloomer, now a student at Archbishop Williams High School in Braintree. "I've also realized the power kids have to make a difference, so that encourages me."

At her new school, Elizabeth began a chapter of a national organization, Operation Day's Work, that has raised thousands of dollars to support children in developing countries. Bloomer's speech to the United Nations was the latest in a public-speaking career that began when she was twelve. She has spoken to a congressional roundtable in Washington D.C. and at Harvard University and other colleges.

With her middle school classmates, Bloomer has also lobbied senators to ratify a new international treaty to discourage child labor, which affects about 250 million children ages five to fourteen. "She's been a relentless voice," said Ron Adams, the seventh-grade language arts teacher whose class Misah visited when he came to the United States. "Elizabeth was a big part of getting kids to be aware of this global treaty." President Clinton signed the treaty in 1999, and it took effect two months ago. "I never intended to be a spokesperson," she says. "There are lot of kids who are spokespersons, too."

Bloomer's passion is driven by a family rule: "Once they are involved in something, we don't let them quit," said her mother, Roberta Bloomer, who has six other children, aged fourteen, twelve, ten, eight, five, and thirteen months. At the UN, Bloomer spoke before 900 high school delegates from around the world. Her 25-minute speech was broadcast on the World Wide Web, and her words were translated into six languages. She will plead that more be done to help children.

And, she told the story of Iqbal Masih and how his life and death spurred her middle-school classmates to raise more than $100,000 to build a school in Pakistan to honour him. "One of our mottos is: A bullet can't kill a dream," she said. "I thought that was horrible that someone would shoot a little boy, probably for standing up for what's right...We're his voice."

Back to the top

Htoo Twins

Asgard

Napster